Gene LeBell, Last of the Sadistic Bastards, Part Two

If you missed Part One of our discussion with Gene LeBell, check it out for discussion about Ronda Rousey, training with Karl Gotch and Ed “Strangler” Lewis, what it means to be a Sadistic

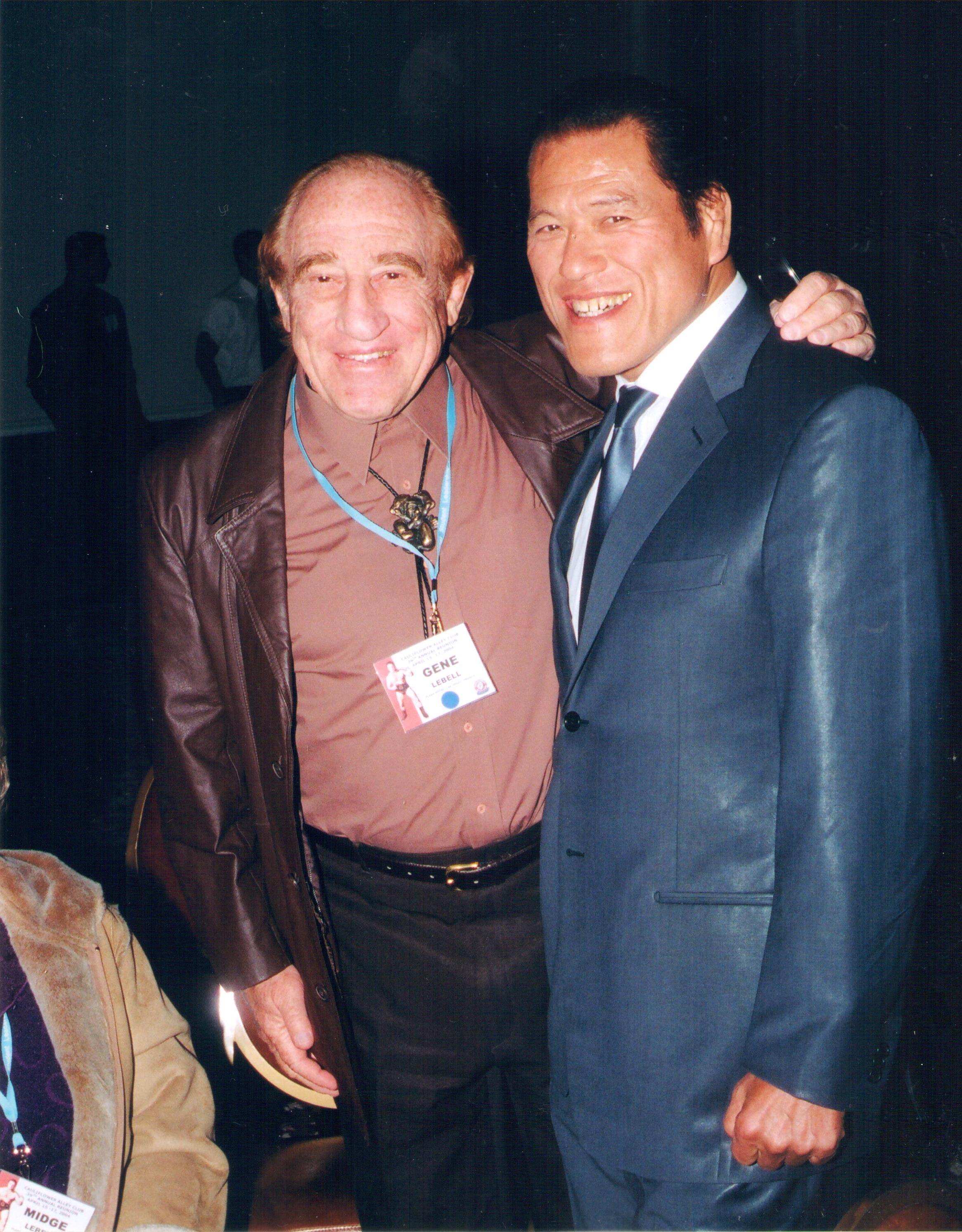

Gene LeBell is a legend for a myriad of reasons. He trained Roddy Piper and Ronda Rousey. He was trained by Ed “Strangler” Lewis, Lou Thesz, and Karl Gotch. He, along with his brother, ran the Los Angeles NWA territory. He took place in the first televised MMA bout back in 1963 and later refereed one of the most famous MMA fights of all time between Muhammad Ali and Antonio Inoki. But one of the most memorable, instantly recognizable things about him is the pink gi that was his trademark

“The true story is I was in Japan at a tournament. Now everybody wears patches but back then nobody had tattoos, nobody had patches…it was just clean white. So I used the gi to work out. And what happened, they washed my gi with something red and it came out pink. So there’s a couple hundred people with white, clean gis at attention. And I’m there, with a pink Gi, and then everybody went “Hohohoho”. And so I thought it was a one time shot. Then they said next day in the Mainichi newspaper, that the daikon wins. And a daikon is like a radish, and I says they’re talking about my red hair. No! They were talking about the gi! So I got a lot of people teasing me and instead of going back to the white gi, I kept the pink one so I could have sexual release when I grabbed ’em by the throat.”

Though LeBell had an extensive background in boxing and wrestling, to much of the combat sports world, he’s best remembered for his accomplishments in judo, and with good reason. It’s not only the discipline in which he trained Olympian Ronda Rousey and her judo champion mother AnnMaria De Mars, but also the one that gave him his nickname, “Judo Gene.”

“I got into judo when I was very young, with the Japanese after World War II. They were very good in competition, and that’s what I liked. I won the nationals a couple of times then I turned pro. Kind of interesting, the local judo group kicked me out because I was doing stunts in the movies. I was shaming Kodokan Judo. Kodokan Judo is very good, but the movies made money. When I did judo, I’d win all my matches. When I did movies, stunt work, I lost all my matches. Now you look at those pieces of tin up there, gold plated, that’s from winning. You look at my bank book, that’s from losing. What would you rather own? A bunch of trophies or enough money to go out and buy a car cash?”

For fans of LeBell’s immense contributions to MMA and professional wrestling, it can be somewhat disconcerting to hear him speak about those fields in what seem like disparaging terms. But more than anything it’s a matter of realism – it’s why he repeated, “Not that it means anything,” and “They don’t mean anything to anybody but me,” over and over again as we toured his house and collections. As proud as he is of his innumerable accomplishments in combat sports, LeBell recognizes that it was his stunt work – appearing in more than 1,000 television shows, movies, and commercials – that earned him his livelihood. And in doing so, LeBell worked alongside countless pop culture icons, including Chuck Norris, Burt Reynolds, Clint Eastwood, Adam West and, on the set of the Green Hornet, a young actor who would become an iconic martial arts star.

“Bruce Lee, he worked out with me for a long time, and I showed him how to grapple. He showed me how to jump and do those things for the movies. That was 35, 40 years ago.”

I was eager to discuss the overlap between fighting as entertainment and fighting as competition – as that murky grey area is where LeBell spent almost the entirety of his career – so I mentioned that Lee is often seen as a forerunner of mixed martial arts. In hindsight, I should have chosen my words better.

“A forerunner? This is a time I feel like bitch slapping you. I was in the first televised MMA bout!”

LeBell was right to have his ire raised. After a bait and switch by boxer Jim Beck, LeBell found himself squaring off against boxer and amateur wrestler Milo Savage in Salt Lake City all the way back in 1963. This was 13

“Don’t play another man’s game. When I went against Milo Savage, they said no kicking. Well, the way I feel about it is, your legs are longer than your arms. You’re out of reach with your hands, but you can kick a man. And you might hit a football 40 yards but you could kick it 70 yards. So if the promoters say you can’t use your legs, they’re cutting down something. It’s like with Ronda. Certain things they don’t want her to do because they’re too dangerous. And I say, ‘Screw it, do it anyway!’ You know? Punish their body.”

It’s a near constant point of discussion in combat

“In a lot of these

jiu-jitsu tournaments, they just recently started allowing leg locks. Good. Knee-locks are okay…but they don’t allow heel hooks. Well, you gotta know heel hooks! Here’s how it works: Lots of people make their own rules because they really can’t tie their shoes on something, you know? So know everything. Beat a man with what he doesn’t know. Beat a man with what he doesn’t know…or can’t counter because he doesn’t know it, doesn’t know what the hell you’re doing.”

“Grappling didn’t have rules. Whatever it took to win. If I had to grab you by the ear or the nose as a handle, so be it. If I grab you in a hold and there’s a pressure point, and it hurts…that’s it. At first in MMA you could pull the hair. Can’t do it now. The rules have changed. Wherever you compete, you gotta go by their rules, and sometimes I think that’s limiting. I don’t believe in eye-gouging, but if you have to use certain parts of a man’s body for a handle…It’s easy to body-slam someone, but you’re not allowed to. But you need to know it. If you don’t know it, you’ll never be the sadistic bastard. You make your own rules. I’ve got hero buttons from all over the world, but the thing I’m most proud of is the Sadistic Bastard, ’cause those guys were the best.”

The lawless grappling that LeBell talks about – as practiced by Sadistic Bastards like Gotch and Thesz – is no longer in vogue, having fallen by the wayside in favor of the UFC’s version of MMA and modern professional wrestling trends. But LeBell still has nothing but respect for the sport that he once promoted and competed in.

“Professional wrestling, to me, is more dangerous than MMA. Because in MMA there’s certain rules. In pro wrestling, if you get slammed out of the ring…I know so many wrestlers, good wrestlers, that do it a thousand times and then one time they’ll get hurt. It’s dangerous, I give it a lot of respect. So anybody says something bad about pro wrestling or MMA, I say, ‘Well, why don’t you come down the to the dojo and let’s talk about it?'”

“Being in pro wrestling you gotta prove that you’re the better man. That’s important in life. If you want to be whatever you are, you gotta be the best. You have the mental capacity, but you gotta get off your gluteus maximus.”

LeBell’s mother, Aileen LeBell Eaton, first got involved with boxing and professional wrestling in her 30s, through the company of her second husband, Cal Eaton. When Cal passed away, Aileen took over for him, promoting boxing and wrestling matches at the Los Angeles Olympic Auditorium. She worked with boxers like Floyd Patterson, Joe Frazier, George Foreman, Sugar Ray Robinson and others, and was instrumental in the creation of wrestler George Wagner’s “Gorgeous George” persona, which established the mold for the preening, arrogant wrestling villain.

After Aileen’s death in 1966, Gene and his brother Mike took over the Los Angeles territory, renaming it NWA Hollywood Wrestling. Together, they promoted events featuring Freddie Blassie, Dino Bravo, Chris Adams, the Funks, the Guerreros, and more. But one of the most significant and most fondly remembered wrestlers to pass through the promotion was Roddy Piper.

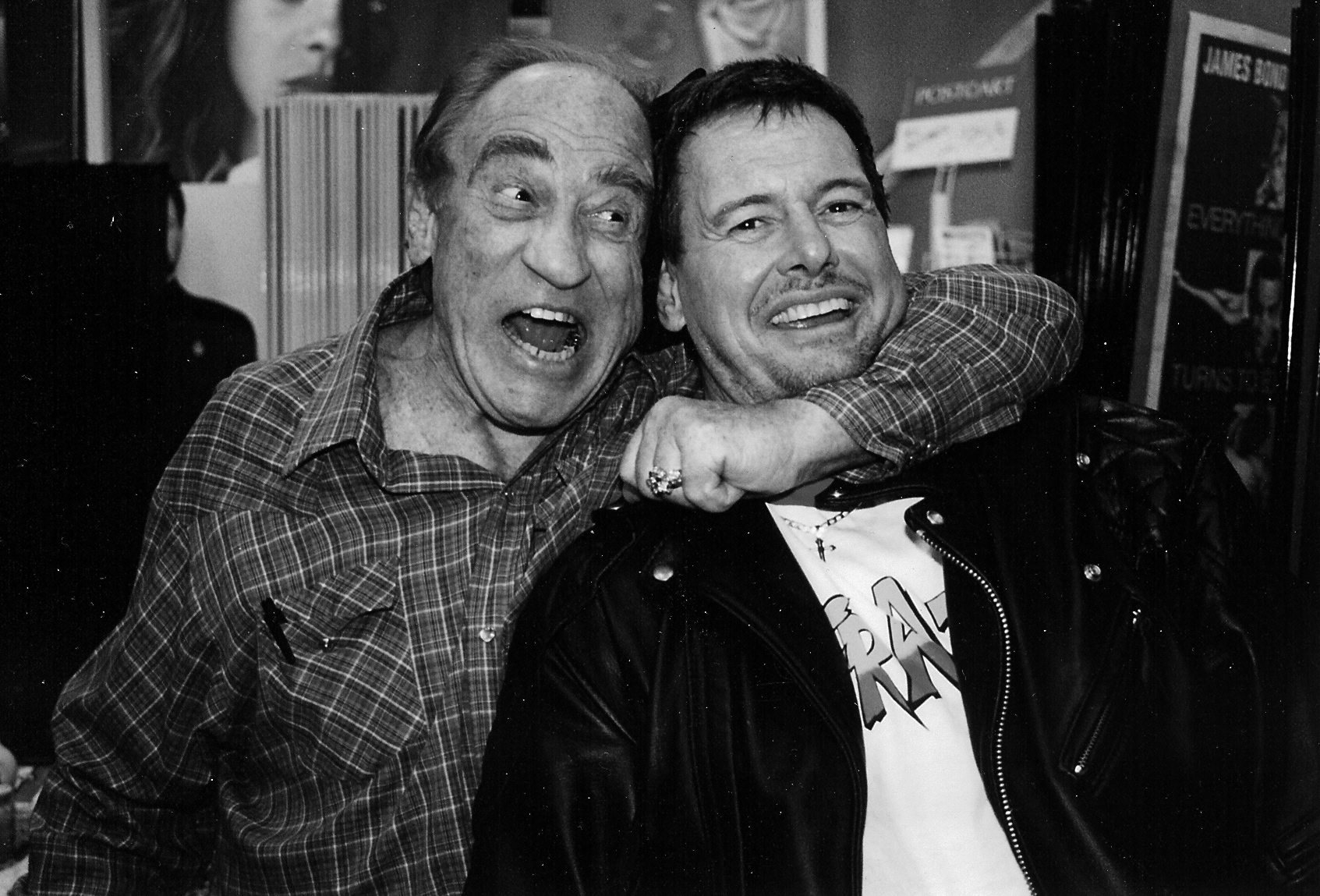

“Great

wrestler , great showman, great friend. He worked with me since he was sixteen. He told everybody he was eighteen ’cause you had to be eighteen to wrestle pro, but he was really sixteen. And when he wasn’t feeling good, he’d call me up and say ‘Let’s go down to the gym, I want to get it out of my system.’ And we did that for thirty years. He had natural charisma. Very natural charisma. And with his talking, he’d create heat, where people didn’t like him. But as my mother used to say, ‘If it sells boletus, go for it.'”

I spent a full afternoon talking with “Judo” Gene LeBell, though truthfully, it was mostly spent listening as he filled me in on

“Ronda knows things that have never been seen before. I have a hold that she hasn’t demonstrated because it’s too dangerous. Only three people know the hold: Rowdy Ronda, Travis [Browne], and Gene LeBell. Don’t let these mere mortals steal it because they’ll say they invented it, and it ain’t happening.”

To anyone familiar with the history of wrestling and combat sports, this is nothing new. Holds have been rebranded, given different names, and then argued over for decades. If you don’t believe me,

“None of your business. This hold here is devastating and you see Ronda wrestle and you think she’s showing you everything. It ain’t so. She’s got secrets, and who are you learn the secrets?”

For four hours, I’d heard the legendary Gene LeBell make oblique references to a secret hold known only to himself and two fighters that he considers family: Ronda Rousey and her husband Travis Browne. I figured that I’d gotten all that I was going to get from him anyway

“Don’t bother me mere mortal. You don’t even walk on water, okay? I made a lot of money many, many years ago in Texas. And this hold…no one had ever seen it before. In Texas I hurt a guy with a variation of it and I had to leave town, you might say. I was married then and the guy grabbed my wife by the ass and I said, ‘That’s not an arena rat, that’s my wife!’ I’m not mentioning his name because he’s a famous wrestler, but we got in the ring and I fucked him up. What can I tell ya? But, well…payback’s a bitch.”

“Your life is 60 or 70 years if you’re lucky. You’re dead for two or three million, so why not make hay while the sun shines? Do what makes you happy. Right or wrong, criticism be damned. It’s your life, you live it.”

I’ve interviewed a lot of big names in wrestling – during my time at WWE.com, at WWE Games, and on my wrestling podcast STRAIGHT SHOOT – so I went into this interview thinking I knew what to expect. Twenty minutes, thirty tops, of Gene LeBell running me through all the talking points: The pink gi, Roddy Piper, his early MMA bout, Ali/Inoki, his stunt work, and, of course, Ronda Rousey. All the same stuff he’s talked about ad nauseam over the years. I figured that if I was lucky, I’d end up with a take that was different enough that my editor would be happy. But instead, I ended up with something far more substantial.

I spent more than four hours with Gene LeBell and while he covered all the obvious ground, what thrilled me the most was receiving insight and life lessons from a man who straddles the line between professional wrestling and

On the surface, it can be a cynical way of looking at things – always searching for the con or the grift, made forever painfully aware of the performance involved with everyday life. But cynicism doesn’t have to lead to fatalism or even apathy, and that fact was clearly on display during my afternoon with LeBell. Even a man literally born into professional wrestling, one of MMA’s earliest frontrunners, has convictions that remain unshakeable. Even a Sadistic Bastard has truths that, amidst all the bullshit, remain sacrosanct.

The best parts of our afternoon together didn’t appear in either part of this extended interview – they were the moments that LeBell directed me to turn off my voice recorder, so that he could tell tales about old friends and enemies, share personal stories, and even give more details on the devastating Judo Gene hold. But I’m not at all sad that those moments couldn’t be included, as it means that the interview exists in that same murky grey area between fact and fiction, just like professional wrestling and combat sports at their best, and I’d say that’s a perfect way to explore the life of a Sadistic Bastard.

Aubrey Sitterson is the author of The Comic Book Story of Professional Wrestling, available wherever books are sold. You can find him at his