Real Shooters: The WWF World Martial Arts Heavyweight Championship

RondaRousey.com’s Real Shooters feature explores the good, the bad, and the weird of pro wrestling-MMA crossover moments in history.

The brief alliance between the World Wrestling Federation (WWF) and New Japan Pro Wrestling (NJPW) produced one of professional wrestling’s most unusual championships. In fact, WWE.com even calls the WWF World Martial Arts Heavyweight Championship—which was active between December 1978 and 1989—one of “10 championships you never knew existed.” Since it was rarely defended and only ever held by two different people, it’s an easy one to overlook. However, the World Martial Arts Heavyweight Championship is worth remembering as a title that produced unique matches and had a connection to both wrestling and MMA history.

NJPW and the then-WWWF (later WWF, currently WWE) began a working relationship in 1975 when both were relatively young wrestling promotions. The companies sometimes shared talent, including New Japan’s founder and top star Antonio Inoki, who first appeared for the American promotion in 1975.

Inoki achieved enough in the WWF to be inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame in 2010 and, technically, to be a former WWE Champion, though his reign is no longer recognized. He defeated Bob Backlund for the company’s top championship in 1978 and lost it back to him a week later. While his reign was officially acknowledged at the time, it currently is not, and has been referred to be WWE as a “phantom title change.”

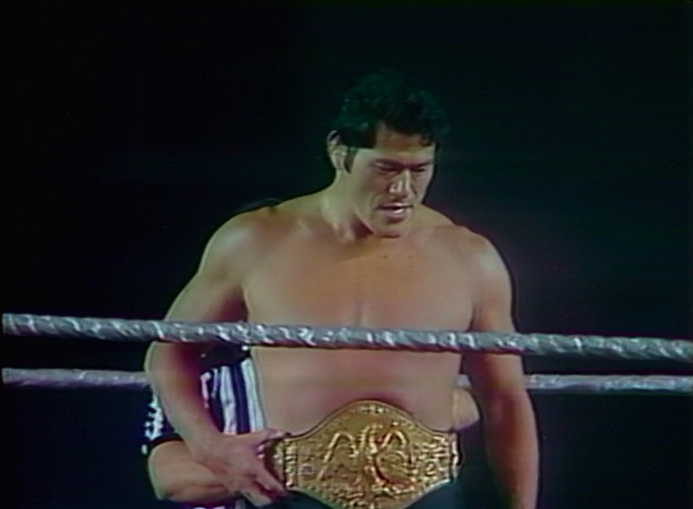

Though Inoki’s short time with WWF’s most prestigious championship has been stricken from the record, he is still recognized as the first holder of a championship the WWF created specifically for him, the World Martial Arts Heavyweight Championship. Much like the WWWF Junior Heavyweight Championship that was reinstated specifically to be won by NJPW’s Tatsumi Fujinami, the World Martial Arts title was created as a way of strengthening the bond between the companies. In 1978, Inoki was awarded this championship by Vince McMahon Sr., not after winning a match but in recognition of his achievements in combat sports.

To explain why the WWF World Martial Arts Heavyweight Championship was the championship created for Inoki requires an overview of his many achievements up to that point. By 1978, he was one of the most popular pro wrestling performers in Japan (just listening to his theme song tells you the sauce he had in the ‘70s) and, by the time he retired, he was undeniably one of the most popular figures in the history of Japanese wrestling. In addition to his in-ring skill, he had the combination of charisma and shrewdness that led to a long career in politics (in the House of Councillors—the upper house of the National Diet of Japan—from 1989-1995 and from 2013 to the present.)

Inoki was also a pioneering promoter of both MMA (he booked, among many others, Shinsuke Nakamura’s first fight) and pro wrestling and wasn’t afraid of a fight himself. He had been trained by Karl Gotch in the art of catch wrestling and his skills were praised by Carlson Gracie. He exhibited his grappling techniques against shoot fighters from a variety of backgrounds, including karate competitor Everett Eddy and boxer Horst Geisler.

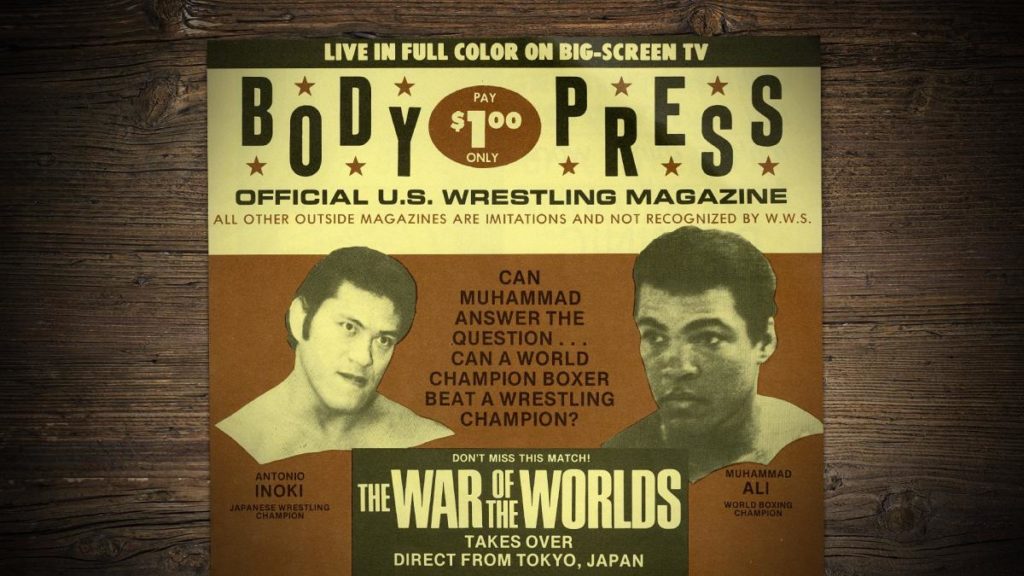

The most famous of these types of bouts was the Antonio Inoki vs. Muhammad Ali—”Wrestler vs. Boxer”—fight in 1976. It wasn’t received well by viewers due to its lack of action, but the fight between athletes trained in different disciplines was a precursor to modern MMA. Many recognized its significance at the time, including WWF management, hence, the WWF World Martial Arts Heavyweight Championship.

The unique championship had a history of defenses that was unusual in multiple ways. First, the inter-promotional, international nature of the title resulted in it being defending much less frequently than other pro wrestling championships: a total of 10 times in its 11-year history. (Cross-referencing “The History Of The WWF World Martial-Arts Championship” by Kris Levin with the defenses available to watch through WWE’s and NJPW’s archives finds four matches for this belt in 1979, and two each in 1980, 1984, and 1989.)

Something else that made this title different was that when Inoki defended it in the United States, he was presented differently than most Asian performers at the time. Characters that drew from broad ethnic, national, and regional stereotypes were more common in pro wrestling in the 1970s than they are today. Japanese wrestlers performing in America were typically villains, depicted using language that recalled World War II and/or older, Orientalist stereotypes. (At the same time, ethnic stereotypes were pervasive in Japanese wrestling as well. Inoki himself had many matches against characters that could be summed up as “evil foreigner.”)

The World Martial Arts Heavyweight Championship was part of presenting Inoki as a rare Japanese hero in the United States. The title said that, though viewers might not understand this man’s culture or language, he was an athlete worthy of respect.

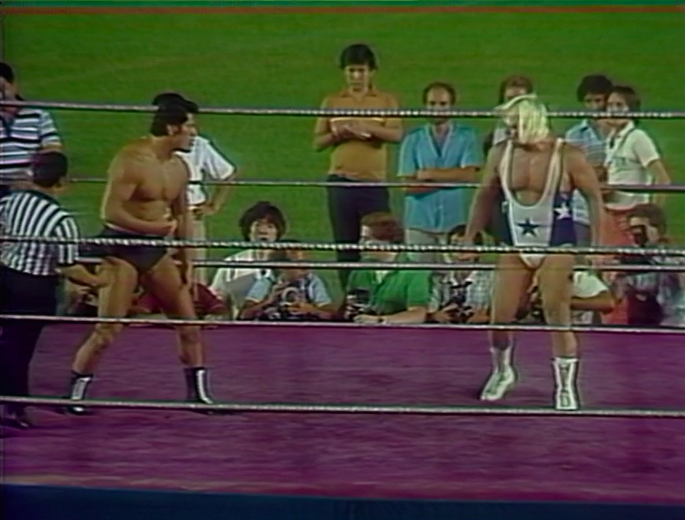

Another key part of this presentation was Inoki being booked against villains in the U.S., like in his title defense against “Pretty Boy” Larry Sharpe at Showdown at Shea in 1980 (a match you can watch on the WWE Network). Inoki vs. Sharpe was a straightforward match with a challenger easy to boo and a champion whose win was deserved and easy to cheer.

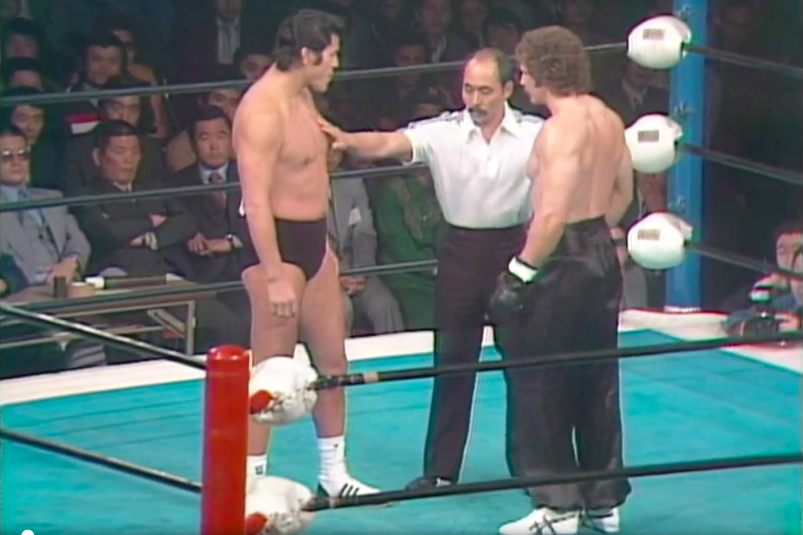

In Japan—where the title was contested only in NJPW after the company’s alliance with the WWF ended in 1985—the defenses looked less like other pro wrestling matches on their cards. Instead, these were presented as shoot fights between martial artists, Inoki using the title picture as a platform to continue his booking experiments from the previous decade. He faced opponents like martial artist and bodybuilder “Left Hook” Mike Dayton, Dutch judoka and Olympic gold medalist Willem Ruska, and karate world champion Willie B. Williams, rather than other professional wrestlers.

Though the winner and loser were decided beforehand like the rest of the card, and the in-ring action didn’t look much like MMA apart from the use of rounds, it looked more like MMA than most pro wrestling at the time. International pairings of wrestler vs. karate master, etc., weren’t presented the same way as typical 1980s NJPW fare and now bring to mind early UFC cards more than most pro wrestling.

The April 3, 1979 Inoki vs. Dayton match for the World Martial Arts Championship, for example, featured some realistic kicks and strikes as well as Dayton bleeding from the forehead after an unprotected-looking headbutt. It also used dramatic devices of pro wrestling, like Inoki being dumped over the top rope during the second round and throwing many headbutts that were clearly worked. It ended by referee decision.

Sporadically for 10 years, Inoki defeated athletes from a variety of backgrounds in these types of matches. Every challenger put up a good fight before falling to the champ. However, in 1989—the last year the World Martial Arts Heavyweight Championship was active—Inoki finally met his match in Shota Chochishvilli, and in doing so, told a story of struggle and sportsmanship that again saw the belt used as a bridge between international organizations.

Chochishvilli was a Georgian judoka who had won gold at the 1972 Olympics and bronze at the 1976 Olympics, as well as several other judo world championships, all while representing the Soviet Union. He only had three pro wrestling matches in his life and they all involved Inoki.

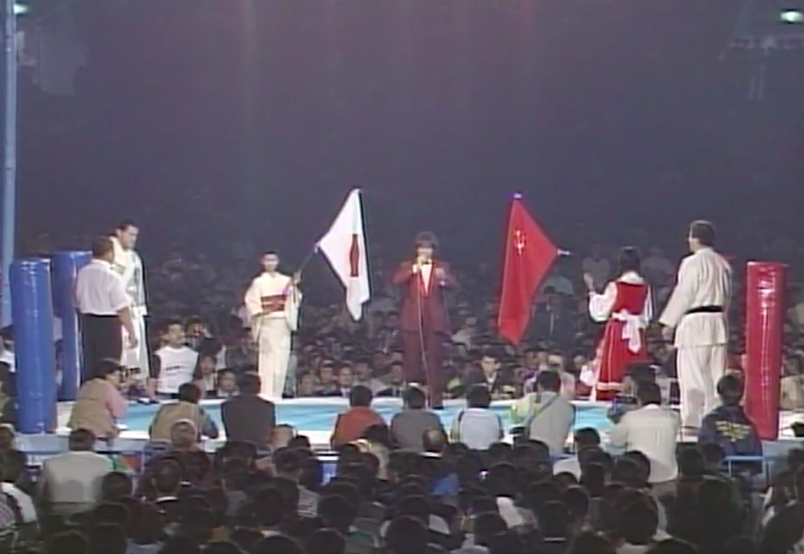

The first was on April 24, 1989, at NJPW’s first show at the Tokyo Dome—the stadium where they now hold Wrestle Kingdom, their yearly WrestleMania equivalent. Both Soviet and Japanese flags were displayed in the ring before the match, emphasizing its international aspect more than Inoki’s previous defenses against non-Japanese opponents.

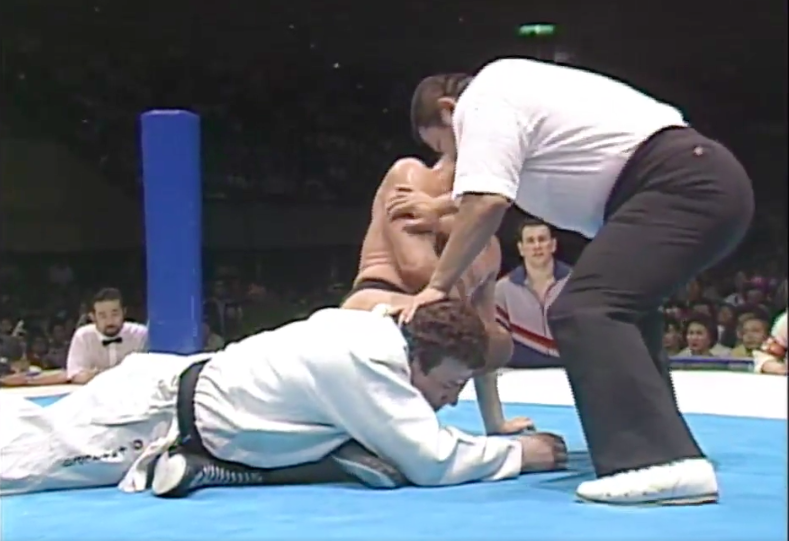

This first Inoki vs. Chochishvilli match holds up as an exciting watch on the strength of its story structure and the champion’s performance. The 46-year-old Inoki landed the first offensive maneuver right at the end of the first round. But Chochishvilli grounded him and dominated in the second and by the beginning of the third, Inoki was clearly in much worse shape than his opponent. Most visibly, one of his arms had been completely immobilized.

Still, Inoki beckoned at his opponent to bring the fight—but as a trick to get him close and off guard enough to land some kicks! The crowd loved this and got more and more hyped as Inoki continued to score offense.

But Chochishvilli was able to take him over and lock on a sleeper hold from which Inoki was very much saved by the bell. He managed to hold his own through the fourth round. In the fifth, Inoki struggled to rise to his feet before the 10-count after a backdrop. He managed to do this again after another backdrop, but the third time with the move turned out to be the charm for Chochishvilli.

A disappointed, exhausted Inoki, having lost the championship he had held for almost 10 years, handed the belt over to his opponent. He had to hold it in his teeth for a moment while they shook hands because he was still unable to use one of his arms. Clearly, these were both athletes to be respected.

What happened in their first match contributed to an even hotter crowd for Inoki vs. Chochishvilli II on May 25, 1989, in Osaka. It almost definitely helped that Inoki’s popularity was at a high point—his political career was underway and he would be elected to the House of Councillors a little under two months after this match. The shot of a man in the audience waving a huge flag set a patriotic tone before the match, a good look for a man running for the Japanese equivalent of the Senate.

This match was much shorter than the one at the Tokyo Dome and started faster with a missed kick from Inoki. Chochishvilli again targeted his arm and locked on a submission right before the end of the first round. But in the second, Inoki quickly submitted the champion with an armbar.

Now it was Chochishvilli who had to hold the belt in his teeth in order to shake hands, Inoki having fully avenged the arm damage from their previous match. The crowd chanted the former champion’s name appreciatively. The last match for the WWF World Martial Arts Heavyweight Championship ended with mutual respect and good sportsmanship—and with Inoki on top.

The epilogue to this feud took place at the first pro wrestling show held in the USSR, NJPW Martial Arts Festival at Central Lenin Stadium in Moscow on New Year’s Eve 1989. Former rivals Inoki and Chochishvilli teamed up against Masa Saito and Brad Rheingans, a wrestler who had represented the United States in the 1976 and 1980 Olympics and would continue to work for NJPW in the ‘90s. The fast-paced tag team match included blatant cheating from the opposing team against the Soviet wrestler.

Inoki and Chochishvilli overcame their villainous opponents after Inoki, now a senator as well as a working wrestler, avenged his partner against the American. He then got Saito away from the ring and tagged in Chochishvilli to quickly get the pinfall victory. One can easily imagine a version of this happening on the other side of the Iron Curtain with the moral alignments of the USSR and USA reversed, but this was the ‘80s rather than the ‘70s and it was the Soviet Union rather than the United States with which Inoki and NJPW were doing business.

When the WWF World Martial Arts Heavyweight Championship was retired that same day, Inoki had held it for 4,000 combined days and Chochishvilli for 31. The title had temporarily bonded two wrestling promotions, resulted in some unique matches, boosted a political career, and turned out to be a preview of things to come in both pro wrestling and MMA. It might be a largely forgotten championship today, but it’s still one worth remembering.